Brands are relative, reputations are absolute

Here at Tovera we continue to think about why corporate brand is different from corporate reputation.

I am struck by how brands declare themselves in terms of providing their benefits without harm, without doing damage, as Google might say, “not being evil”. The “extracting the negative” approach. Clearly this is because the brand is – and should be – focussed on the distinctive offering that makes its user prefer it and recognising that it should demonstrate awareness of potential harm. This acknowledges the power of the brand and its interventions.

On the other hand, corporate reputation is always expressed in the language of business striving to do good. This applies whether it’s societal or commercial good, it’s always about “adding the positive”.

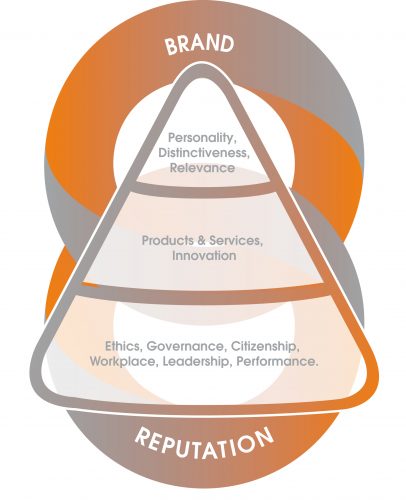

Some while ago Helen Edwards suggested a Hippocratic oath for brands. She suggests that this oath would be “the one boundary that must never be crossed” about a) not harming the brand and b) not harming consumers or society at large. For me, that’s where the brand and reputation distinction come into play again. This is not meant to make a false distinction – brand and reputation are after all part of one holistic entity and entirely dependent on each other – but it again shows how the reputation element deals in absolutes: are we good, well governed, adhering to regulations designed to ensure no harm is caused by our actions etc, while the brand is viewed in relativities – are we more/increasingly famous, more distinctive, more relevant, etc

We might be aiming to be fairer (Fair Trade), purer (Innocent), healthiest etc but those challengers and disrupters that shape the next iteration of a category find that if they do strike a chord and tick the relevant box, then competitors will be fast into their newly created space. And what was newly kind to us and our society/environment starts to become the expected and slips into the way we do things, the reputation absolute.

On the negative side, if our generic marketing activity (promotional, price cutting etc, not our distinctive brand story) encourages increased consumption of something intrinsically bad for us or for society at large, then ultimately the brand image and sales suffer, is that not right? Well not necessarily, as sales may remain high while we concentrate on giving consumers what they want (tasty salty snacks, sugary drinks, etc). So it has to be the better part of the corporate entity that comes into play – we might call it the conscience – and that in turn might be thought of as the part that considers its reputation.

So when we plan, develop and assess our brand and reputation strategy, we can open our minds to the range of possibilities for development and growth of the brand while safe in the knowledge that our parallel commitment to a solid reputation will keep us honest. And ultimately, this is the approach that will ensure the long term success of a company or organisation.

By Ann Binnie, Managing Partner.