Philosophy

The founding idea that underpins the TOVERA Consulting methodology is based on the work of Ann Binnie and Spencer Fox. Below is a paper written by Spencer and Ann wherein they share their thinking, their strongly held belief and evidence that Brand and Reputation must be considered together.

Completing the picture – the reputation and brand story.

Binnie & Fox, 2015.

Introduction.

An organisation’s brand and reputation are both proven to contribute to its value and be fundamental to its long term success.

The working hypothesis of this paper is that while most work in this area has tended to focus either upon the brand OR reputation, the most successful companies in the long run are those that work towards having both a strong brand and a solid reputation. To have weakness in either poses a risk to an organisation, if not immediately, then certainly in the future.

The work of Binnie & Fox formalises their belief, borne of considerable experience with both brand and reputation, that the most effective approach is one which takes account of the thinking and practice around both. They bring together and further develop the latest (and/or what they consider to be the best) thinking from the worlds of reputation and brand and explain how – as both are critical to business success – they should be considered in a single framework. This is not to suggest that there is a simple – or worse, simplistic – answer that distils the complexities of both into one view, rather that this framework recognises the interdependence of each and the power of their successful symbiosis.

Background

Brand value is a well-documented subject. Whilst there are some differing approaches on how to measure brand value, it is now widely accepted that a large proportion of a company’s intangible value relates directly to the value of its brand (or brands). For example, a study by Interbrand in 2014 and published in Forbes magazine in that same year, found that Coca Cola’s market value was $169billion and of that, $81.5billion was directly attributable to its brand. That equates to over 48% of Coca Cola’s market value. Whilst this equation is more pronounced for consumer facing brands, there is a similar picture for b2b brands. The same study found that IBM’s market value was $161billion and of this $72billion was due to the value of its brand which is more than 44% of its market value. Similarly, of Accenture’s market value of $52billion, 20% is attributed to its brand value at just over $10billion.

A well respected familiar construct in the world of branding is Y & R’s Brand Asset Valuator and its Power Grid [fig 1] that demonstrates four pillars of branding: Differentiation, Relevance, Esteem and Knowledge. The Power Grid shows that those brands that succeed boost their brand strength with high differentiation and relevance and that powerful leading brands build esteem and knowledge over time.

We can revisit this model to refine our understanding of the relationship between brand and reputation in the specific context of the corporate brand. We could quite logically re-label the dimension of brand stature (Esteem and Knowledge), arguably more accurately, as reputation weight, because for sustainable business growth and leadership, brand strengths of relevance and differentiation depend upon a stable basis of reputation, defined as esteem and knowledge.

Reputation is fundamentally about the knowledge (based on either fact or perception or a mix of both) an individual has about an organisation and the expectations that are built on that knowledge. Reputation is slower to build but once established, a powerful asset in the service of continued growth and leadership.

Reputation – independent of brand – has also been accepted as a component of intangible value of a company’s balance sheet. As in some brand valuation methodologies it is often referred to as ‘goodwill’ in accounting terms. However, more recently reputation has been considered as a much broader concept. A good way of demonstrating this is to consider the volatility of markets from the 1960’s through to today.

A study of the Standard and Poor’s 500 index (S&P500) of the biggest companies in the USA between 1960 and 2010 reveals an interesting picture. In the period between 1960 and 1980 the market grew in a slow, steady and incremental way. During this period there was very little volatility in the market. This period has been defined as a time where market power was in the hands of corporations. That is, customers and wider stakeholders had to rely on the information that corporations chose to share; corporations were able to keep a fairly tight control on how they were perceived.

This period was also characterised as a time where the market value of corporations was tied closely to their tangible asset value. A study by Ocean Tomo[1] found that on average, 83% of company value during this period was tied to tangible assets such as cash, investments, buildings, and production lines. In that regard, as well as having a tight control on information about their company and their dealings, fluctuations in a company’s value were small and unlikely to fall below the value of its tangible assets. In this context, reputation (as a driver and protector of value) wasn’t considered a priority and very few companies considered reputation management as anything more than information management.

This period was also characterised as a time where the market value of corporations was tied closely to their tangible asset value. A study by Ocean Tomo[1] found that on average, 83% of company value during this period was tied to tangible assets such as cash, investments, buildings, and production lines. In that regard, as well as having a tight control on information about their company and their dealings, fluctuations in a company’s value were small and unlikely to fall below the value of its tangible assets. In this context, reputation (as a driver and protector of value) wasn’t considered a priority and very few companies considered reputation management as anything more than information management.

Things began to shift from the 1980’s and in to the mid 1990’s. During this time the S&P500 began to be influenced by the effects of new enabling technologies, most notably that of the mobile ‘phone. People were now able to exchange information faster and more freely. These new technologies helped fuel faster growth but also greater volatility, as investors and other interested parties were able to find out information about companies, share information and respond much faster than ever before.

From the mid-1990’s to the present day the market transformed once again as the full effects of the internet age took hold. At the same time there was a transition in the value of companies where by now over 80% of the average value of a company in the S&P500 was deemed intangible asset value. This intangible value had been built through highly effective IP, Human Resources, brand and reputation strategies. All of this combined had fuelled rapid growth but also extreme volatility. Now a company’s value had the potential to fluctuate wildly within its intangible asset value. The only way to protect this value emerged as strategic reputation management: ensuring a company established and maintained a strong reputation with all its critical stakeholders.

From the mid-1990’s to the present day the market transformed once again as the full effects of the internet age took hold. At the same time there was a transition in the value of companies where by now over 80% of the average value of a company in the S&P500 was deemed intangible asset value. This intangible value had been built through highly effective IP, Human Resources, brand and reputation strategies. All of this combined had fuelled rapid growth but also extreme volatility. Now a company’s value had the potential to fluctuate wildly within its intangible asset value. The only way to protect this value emerged as strategic reputation management: ensuring a company established and maintained a strong reputation with all its critical stakeholders.

Bringing Brand and Reputation together

Building intangible value in a company is both an opportunity and a risk. The opportunity exists for companies to build value through a relevant and differentiated brand positioning founded on an established and trusted reputation. The risk is that when companies get this wrong, when they suffer an event that undermines their brand or reputation, then it is the entirety of their intangible asset value that is at risk. And when that equates, on average, to 80% of a company’s value, we can see how important it is for a company to really understand both its brand positioning and also what defines its reputation across its critical stakeholder universe.

And it’s not just share value that’s at stake. The same issues face private companies and not for profit organisations. Business models can be easily derailed when people withdraw their support. Whether it’s the general public losing faith in a charity because of an accounting scandal or a government and regulator restricting the business plan of a company over concerns about the way it is run – support from stakeholders is critical to business success.

Today, we live in a world where the average person can easily access information about a company: its ownership structure, its investments, its leadership, it values, its profits and so on. They can make informed value judgements on a company and decide whether to give or retract support for that company. Not only that, but individuals now have the platforms upon which to amplify their views to mass audiences. Power to influence company value has shifted from corporations towards individuals.

For some organisations there has been a tendency to view their corporate reputation as distinct from their brand. In today’s world this has become almost impossible given the trends indicated above. Also there is a growing trend for companies to operate brand architectures that are closer to a branded house rather than a house of brands.

So it now seems timely to consider both brand and reputation together. Companies need to harness the power of both and achieve a balance between them as a central tenet of their business strategies.

Approach

The Binnie Fox model considers and distils our understanding of and experience with the various models and methodologies from the worlds of brand positioning/valuation and corporate reputation measurement.

There are respected and effective methodologies to be found in both fields, however they are lacking when considering the effects of brand and reputation together. There is a tendency for reputation models to place great emphasis on rational factors, while in contrast brand models tend to focus on emotional elements.

It seems clear to us that the way people make decisions on whether to buy from, advocate, trust and support a company is complex and based on both emotional and rational factors and these in turn are also influenced by cultural, environment, tribal, religious and social factors.

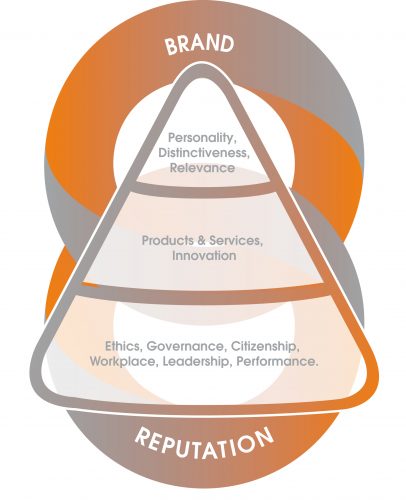

The Binnie Fox model brings both brand and reputation factors in to a single framework for consideration. Very broadly, it can be conceptualised as a pyramidic figure that places the core elements of reputation towards the base and the core elements of branding towards the apex.

It builds on the generally recognised core dimensions of reputation, best exemplified in the RepTrak® model developed by academics Prof. Charles Fombrun and Prof. Cees van Riel, and positions them towards the bottom of our model. Those dimensions relate to corporate culture and behaviour and we refer to this as the Foundation. These are the aspects of a company that cover ethics, governance, citizenship, leadership, workplace and financial performance. These are the areas that a company must get right in order to build a solid base of support from its wider stakeholder universe. All companies have a reputation within these categories of activity – without clarity, strength and a plan to manage these areas the company is on weak ground.

Companies that understand the importance of reputation will strive to build a strong reputation through the pursuit of excellence in these areas.

The next tier is products & services and innovation. These aspects are elevated above corporate behaviour. We place them there as a company’s output is the most important factor for it to get right. It must have good products and services that satisfy customer needs that are relevant and differentiated from the competition. Importantly, in order to maintain quality, relevance and differentiation it must be open to new thinking and behaviours, ie be innovative. These are also the aspects touched by the most stakeholder groups.

Reputation Institute’s annual RepTrak® surveys from 2009 to 2014 consistently found that perceptions of products and services are the single most important of the seven dimensions of its RepTrak® model in driving consumers’ stated likelihood to support a company. Interestingly, in a growing business a company can make up for a weaker reputation foundation if it is particularly strong in products and services. Two good examples are Amazon and Apple. Both have benefitted from the halo effect of being highly innovative and having a great product and service offering. This is despite both having suffered a number of negative reports related to corporate behaviour. Accusations of tax dodging, unfair treatment of employees and aggressive corporate practices have dogged both companies. And whilst consumers and stakeholders believe these issues to be important, most will still buy from Amazon and Apple as they perceive them to have excellent products that satisfy their needs.

However, what this does reveal is a potential risk. Should a company that has driven growth by having great product innovations whilst also having a weak reputation foundation, ever suffer an issue that compromised either the reality, or the perception, of its product and services, then it has nothing to fall back on. This is when support begins to deteriorate and entire businesses are put at risk.

We can point to examples such as Sunny Delight, Starbucks and BP, all of which invested heavily in building powerful brands without first ensuring a solid reputation foundation. After the gulf oil disaster, BP was accused of unethical behaviour and trust in BP evaporated. It was found not to have done enough to fix a bad safety record and risk-taking behaviour amongst some of its employees was shown up. BP lost $billions, it lost market value and market share and some estimate that it will take 20 years to fully recover.

Sunny D invested £10million in building a brand positioned as a fun healthy drink for kids, placed in the chilled cabinet to make it appear ‘fresh’ when in fact it was revealed to contain more sugar than a can of Coke. Consumers felt cheated; consumer groups rallied against it and sales collapsed, prompting its parent, P&G, eventually to sell it at a loss. Starbucks was one of the first big global corporations to suffer accusations of tax avoidance and has had to work hard to recover trust amongst a large part of its customer base in the UK. These are all reputation failures. Had these companies first sought to keep a check on the reputational issues that matter most to customers and other stakeholders, they would have been able to address these issues before disaster struck – they could have built a solid reputation platform to support their brands.

At the apex, we see the upper part of the model through a branding lens and we focus on the relevance to the audience of the company’s offer, whether their needs and wants are delivered by the products and services offered.

At the apex, we see the upper part of the model through a branding lens and we focus on the relevance to the audience of the company’s offer, whether their needs and wants are delivered by the products and services offered.

However, it is not enough to simply be delivering quality, supported by a strong reputational foundation. To be sustainably successful the company needs to be meeting needs in a distinctive way, or meeting distinctive needs (or both!).

Otherwise the company’s proposition, while being a good generic, is vulnerable to being copied, undercut in price, or otherwise displaced in the marketplace.

So the apex of the pyramid gives us the two primary aspects that ensure the corporate brand stands out from the crowd: its distinctiveness and its personality.

In Summary

We envisage the reputational aspects as both a strong, weighty foundation that gives the corporate brand roots and as the fuel and power that helps propel the brand in its distinctive direction of travel.

Balance is required – if the brand is strong and distinctive but its reputation is weakly rooted, the brand could lose its way, not having the necessary support from all its stakeholders.

If the reputation is strongly rooted in important (but generic) aspects but the brand proposition is unclear or not distinctive, the whole brand could lose, or fail to gain, traction in the marketplace. Both scenarios lead to a loss of support from either customers or stakeholders or both, and ultimately result in an erosion of value.

So we envisage the ideal scenario as one of solid reputational foundations acting as strength to support and power to energise the delivery of the stakeholders’ needs in the marketplace, moving in a clear and distinctive direction set by the brand vision.

Operationalising the approach.

The Binnie Fox model provides a conceptual framework for organisations to consider the questions: what are our strategies in each of these areas? What is our reputation foundation? Our product and services? Our brand position? Do we have a strategy that ensures all elements work together? Where are our strengths and weaknesses? How to we compare to competitors and other best in class organisations?

To answer these questions, underpinning the model is a research framework that can be used to both give a measure of reputation and brand strength and also provide the actionable insight to brand and reputation strategies.

This is the basis of the approach, which underpins the consulting methodology of Tovera Consulting.

[1] http://www.oceantomo.com/blog/2015/03-05-ocean-tomo-2015-intangible-asset-market-value/